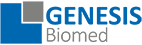

21 Mar Interview Rafael Cantón – Head of the Clinical Microbiology Service at the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital

Rafael Cantón: “It is now, when there is no imminent pressure of a public health emergency such as with SARS-CoV-2, that we have to continue working to promote protocols to deal with these situations”.

Dr. Cantón is since 2011 Head of the Clinical Microbiology Service of the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital and Associate Professor of Clinical Microbiology at the Faculty of Pharmacy of the Complutense University (Madrid, Spain). His research has resulted in more than 600 scientific publications in medical journals and he has participated in 58 book chapters. Dr. Cantón has also been president of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) (2015-2017) and president of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (2012-2016). He is currently a member of the scientific advisory board of the Joint Programme Initiative on Antimicrobial Resistance (JPIAMR) of the European Union and Clinical Data Coordinator of EUCAST. He is also an active member of the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID), is on the Editorial Board of several Microbiology journals and has been editor of the SEIMC Clinical Microbiology Proceedings.

Do you think our national health system is now better prepared after SARS-CoV-2 to deal with a future public health emergency?

In general, there is greater awareness among the population of possible emergencies and among health authorities, technicians and professionals. However, an opportunity has been missed to continue working at the political level to promote working protocols and actions to respond to these emergencies. It is now, when there is no presumably imminent pressure, that actions must be taken to reinforce the system. Primary care, hospital emergencies, training and availability of professionals, and information systems should be priority areas. If we are talking about micro-organisms with the capacity to generate these alerts, continuous attention must be given to microbiological diagnosis and the training of specialists in Infectious Diseases with the creation of this speciality.

Do you think that the creation of the HERA (Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority) at European level in 2021 could lead to an improvement in surveillance and coordination at European level?

My response is positive. In fact, the capacity of laboratories and Microbiology Services in sequencing techniques has been strengthened. It has been applied initially to SARS-CoV-2 but also to other epidemic respiratory viruses. This action may also benefit RedLabRA – The Network of Laboratories for the Surveillance of Resistant Microorganisms, promoted by the National Plan against Antibiotic Resistance (PRAN) of the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS).

How will climate change affect the emergence of hitherto non-existent viruses in continents such as Europe (e.g. vector-borne transmission diseases)?

Climate change may favour the development of vectors (arthropods) that allow the transmission of zoonotic viruses. This fact must also be seen in the context of increasing globalisation and the risk of such emergencies. An example of this is what happened years ago with Zika virus in Brazil, Nile fever in the United States and the risk of epidemic outbreaks of dengue, yellow fever or Crimean Congo in Mediterranean countries.

What are the current challenges to be addressed in the area of antimicrobial resistance to antibiotics?

The challenges to be addressed are diverse. In the field of antimicrobials, the availability of compounds with new mechanisms of action, facilitating access to molecules already approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and implementing innovative reimbursement systems for pharmaceutical companies that introduce these drugs into the therapeutic arsenal. We must also have rapid diagnostic techniques with microbiology laboratories with 24×7 care. We must also have professionals trained in PROA programmes (programmes for optimising the use of antimicrobials) to facilitate better use of these drugs. A no less important aspect is the awareness of the general population in the use of antimicrobials. All these actions have to be carried out in a One Health perspective that also encompasses the veterinary and environmental sector.

What unmet needs are there in the prevention and diagnosis of infectious diseases, and can the use of AI help us to develop new tools in this field?

We have better techniques than years ago, but there is still room for improvement. Facilitating syndromic and differential diagnosis is already a reality, but aspects related to response times and automated work processes such as “random access” need to be further developed. AI can help us in the development of new tests, their optimisation, the analysis of results or the choice of the patient who can best benefit from them.

Can mRNA-based vaccines accelerate the development of new vaccines for emerging viral infections?

They have certainly been an example of their usefulness and have paved the way for possible new vaccines and their development. They have proven to be effective and safe, and the development of new mRNA vaccines should be a priority in policies to prevent emerging viral infections.

Are there any promising technologies that we need to keep an eye on, both therapeutically and diagnostically, in the field of infectious diseases?

There are many initiatives in this field that need to be considered. One example is innovation in the diagnosis of sepsis, although microbiological culture is still necessary. Rapid techniques are being developed based on flow cytometry, microscopy, fluorescence or cantilever sensors that drastically reduce response times. Ultra-fast sequencing systems are also techniques to be considered.