02 Dec Drafts of the Science Law and the Start-ups Law

An Opinion Piece by Josep Lluís Falcó– Managing Partner and CEO at GENESIS Biomed.

Traditionally in Spain it has not been easy, compared to other countries, to create a start-up company, even less to create a technology-based start-up company (EBT).

Unfortunately, the current legal frameworks, such as the Law on Science, Technology, and Innovation (14/2011, hereinafter the “Science Law”) or the Law on Incompatibilities (53/1984) do not offer many facilities to those entrepreneurs who want to take the plunge and start a new start-up.

Let us remember that, to give an example of this lack of facilities in our legal framework, the Incompatibilities Law establishes in its articles 12.1.b, 12.1.d and 16 that personnel belonging to public institutions cannot develop private activities, belong to boards of directors, hold positions in companies and participate in the capital of the company with a percentage of more than 10%.

The drafts of the new Science Law and the new Startups Law, after having analysed them, do indeed offer improvements over the current legal framework, but there is still a long way to go to improve and offer real advantages to technology-based entrepreneurs. In this opinion article we will analyze the most important aspects of each of the drafts and put them in context, looking at those that can still be improved.

New draft of the Science Law

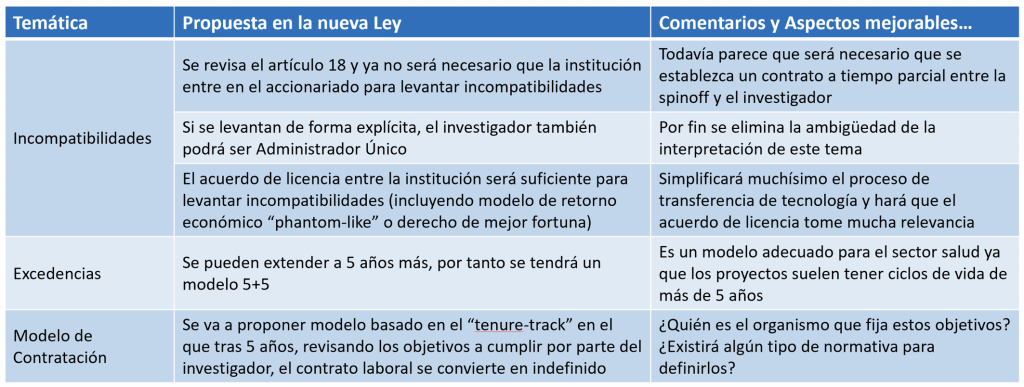

In this draft, the first substantial change that we detected is the revision of Article 18 of the current Law. We note that it will no longer be necessary for the institution that originates the technology to necessarily become a shareholder of the new TBE (technology-based company) in order to lift the incompatibilities of those researchers who are subject to them. Let us remember that this aspect was essential in the current legal framework, and in some cases, it was a clear inconvenience or problem for those institutions that, due to their technology transfer policy, do not usually take shares in the TBEs they generate.

This aspect is relieved by the possibility of lifting incompatibilities directly through the technology license agreement. Indeed, in order to simplify the technology transfer process, the technology license agreement itself, signed between the Institution or Institutions that generate the technology and the TBE, will be sufficient to directly lift the incompatibilities of the researchers. This can be achieved by including economic rights of return to the Institutions in the license agreements. This economic right can, for example, be materialized in a plan similar to a phantom share for the institution.

If we look more closely at this aspect of incompatibilities, we also see that the other major condition currently necessary to lift the incompatibilities of the researchers, the contractual link between the TBE and the researchers, is not eliminated. It still appears that it will be necessary a part-time contract to be established between the TBE and the researchers involved. This, which is not usually a major drawback, is a barrier in itself that could be removed from the current draft.

On the other hand, what is well achieved is that the incompatibilities that made it difficult for researchers to be the Sole Administrators of the EBT have been explicitly lifted. The ambiguity in the interpretation of this issue has finally been eliminated.

Another major matter that seems to be simplified and, in a way, improved, is the management of leaves for those research personnel who request it in order to have a number of years to devote to the EBT, without jeopardizing an eventual return to their original position. In this sense, it is extended by 5 more years to the 5 years already contemplated in the current legal framework.

Finally, and outside the framework of the EBTs, we comment on an issue that has caused a great stir in the research community, and which we have no doubt will continue to do so: hiring models. The draft of the new legal framework proposes a model based on the “tenure-track” already implemented in other Anglo-Saxon countries, whereby after 5 years of a temporary contract, the objectives that the researcher undertakes to meet will be reviewed, and if they are indeed met, the contract will automatically become indefinite. This model, which may apparently offer employment stability to researchers, does not resolve key aspects such as who sets and decides these objectives or whether there is any type of regulation or rule that may define them, among other aspects that generate controversy.

Therefore, after this analysis, we can conclude that, although the incompatibility regime can be considered simplified, there are other aspects that still deserve a further revision cycle in the current draft, and that deserve to be improved, in order to have a new optimal legal framework for the research community that also wishes to create a TBE

Nuevo borrador de la ley de startups

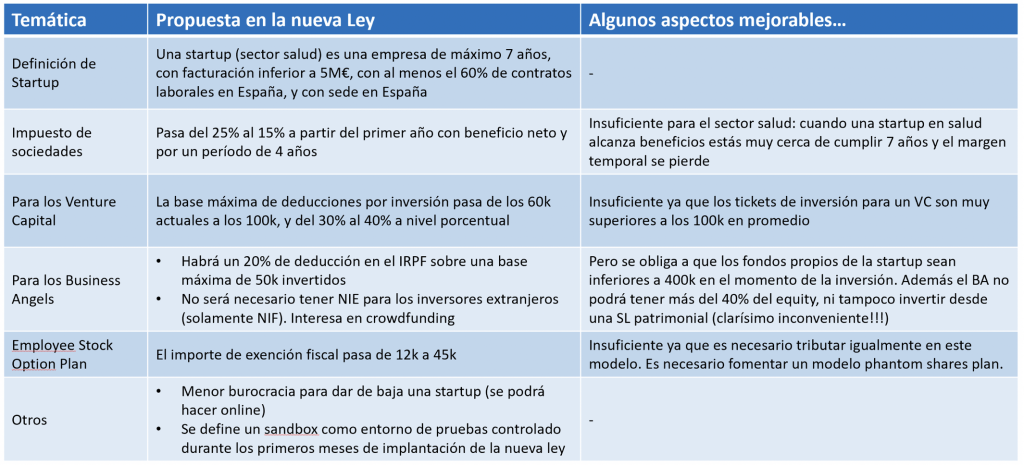

Lo primero que nos encontramos cuando revisamos el borrador de la nueva Ley de Startups es que se define una startup como aquella empresa de máximo 5 años, prorrogables a 7 años en algunos sectores como el nuestro, el sector salud. Además, se incorpora a la definición que dicha empresa, para ser considerada startup, deberá tener una facturación inferior a 5 millones de euros, disponer de al menos el 60% de contratos laborales en España, y con sede también en nuestro país.

Automáticamente todo lo que modifica este borrador de esta nueva Ley solamente aplicará a las empresas que sean etiquetadas como startup, y veremos a continuación que este período de 7 años, en nuestro sector salud, puede ser insuficiente.

En primer lugar, hablemos del Impuesto de Sociedades. Este impuesto pasa del 25% al 15% a partir del primer año con beneficio neto en la empresa, y se extiende a lo largo de los 4 años siguientes. Este hecho, para el sector salud, es insuficiente: cuando una startup en salud alcanza beneficios está ya muy cerca del cumplimiento de su séptimo año, y por tanto de quedarse fuera de esta mejora fiscal. Claramente vemos que los 4 años se pueden quedar muy cortos si consideramos que una startup en salud requiere de, al menos, 1-2 años para completar su fase no regulatoria y 3-4 años más para desarrollar el producto desde el punto de vista regulatorio (estamos hablando, como mínimo, de un medical device de “baja complicación”, por ejemplo).

Por otro lado, para los inversores del tipo Venture Capital, la base máxima de deducciones por inversión pasa de 60k a 100k, y del 30% al 40% a nivel porcentual. Este hecho es claramente mejorable si tenemos en cuenta los tickets promedio de los inversores de este tipo en rondas de inversión estándar.

Si nos fijamos ahora en los inversores Business Angels, vemos que el nuevo marco legal propuesto hace que dispongan de un 20% de deducción en el IRPF sobre una base máxima de 50k invertidos. Además se elimina la obligatoriedad de disponer de NIE para aquellos inversores con distintas nacionalidades, siendo este hecho de alto interés para campañas de crowdfunding. Sin embargo, se obliga a que para poder acogerse a estas ventajas fiscales, los fondos propios de la startup en la que se invierte sean inferiores a 400k en el momento de la inversión. Además el Business Angel no podrá ostentar más del 40% de participaciones sociales, ni tampoco invertir desde una sociedad (patrimonial). Esto supone una clara desventaja para este tipo de inversores ya que la gran mayoría, o al menos los Business Angels con mayor track record en inversión, lo hacen desde un vehículo societario.

Otro tema de clara discordia es el Employee Stock Option Plan (ESOP, plan de incentivos para los emprendedores y empleados clave). Con el nuevo marco borrador se amplía el importe de exención fiscal de 12k a 45k, pero este hecho es claramente muy insuficiente ya que se mantiene la necesidad de tributar por este modelo, cuando hay que tener en cuenta que la mayoría de veces en que el beneficiario de un plan de ESOP reciba participaciones sociales, este hecho puede no estar vinculado a un evento de liquidez en la startup, por lo que la necesidad de tributar y pagar impuestos puede ser un inconveniente para el emprendedor. Todavía se sigue poniendo de manifiesto la necesidad de disponer de métodos alternativos como el phantom share plan, mucho más ventajoso a nivel fiscal para el emprendedor.

Otros aspectos del borrador de la nueva Ley de Startups se basan en la simplificación de las barreras administrativas y en la facilitación de todo el proceso de creación de la empresa en su conjunto. También se define un sandbox como un entorno de pruebas controlado durante los primeros meses de implantación de la nueva ley. Recordemos que esta iniciativa ha funcionado en otros entornos, pero que necesariamente puede no funcionar en el entorno del sector salud.

Lamentablemente, y al igual que en el análisis del borrador de la nueva Ley de la Ciencia, por lo que respecta a la nueva Ley de Startups vemos que existen puntos de mejora clarísimos, sobre todo pensando en las EBTs del sector salud.

Josep Lluís Falcó

Managing Partner & CEO at GENESIS Biomed